By the late 1980s, Combs had already established himself as a powerful tastemaker, sourcing talent and shaping careers, most notably those of Mary J. Blige and Jodeci.

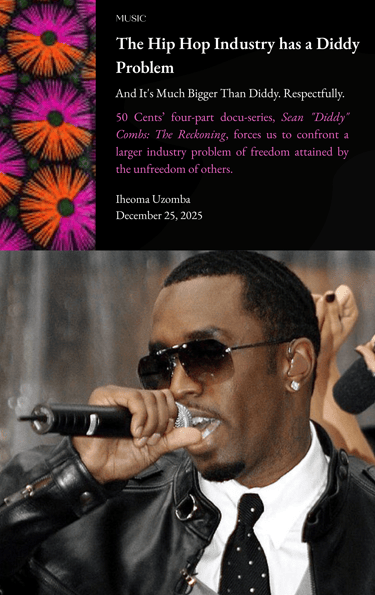

This origin story matters because hip hop loves an ascent narrative. It reveres the climb: from the hood to the penthouse, from intern to mogul, from Harlem to the global stage. The kid who made it out, the hustler who outworked the system, the Black man who built an empire. The Reckoning leans into this mythology generously, reminding viewers again and again of what Puff gave to the culture: hits, platforms, proximity to power, and most importantly, a vision of Black wealth.

But what the series ultimately exposes is not just what Combs gave, but what the industry quietly agreed he could take. And what he took most consistently was not just money, bodies, or loyalty; it was silence.

Hip hop did not invent silence. Of course. But it has perfected the art of dressing it up as loyalty. We are often told that the culture has codes like no snitching, and handle things in-house, or mind yo business.

These codes would explain why men like Diddy remained untouchable for so long. But even more, what the documentary shows is that silence was also economic. It was the cost of access.